When building codes mandate individual water heaters in every unit, they don't just set a standard—they eliminate six cheaper alternatives. Shared heating systems, on-demand point-of-use heaters, solar thermal arrays, heat recovery from greywater, and thermal battery systems all become regulatory non-starters. The average household spends $400-600 annually on water heating that could cost $100-150 with approved alternatives. The difference flows to utility companies and equipment manufacturers who benefit from the mandate.

When a squat toilet gets dismissed as backward, we're not just making a cultural judgment. We're removing a potential solution from consideration—one that requires no water, improves elimination posture, costs almost nothing to build, and eliminates the need for expensive sewer infrastructure. Meanwhile, Americans spend $11 billion annually maintaining aging sewer systems that only exist because we chose one specific sanitation approach and made it mandatory.

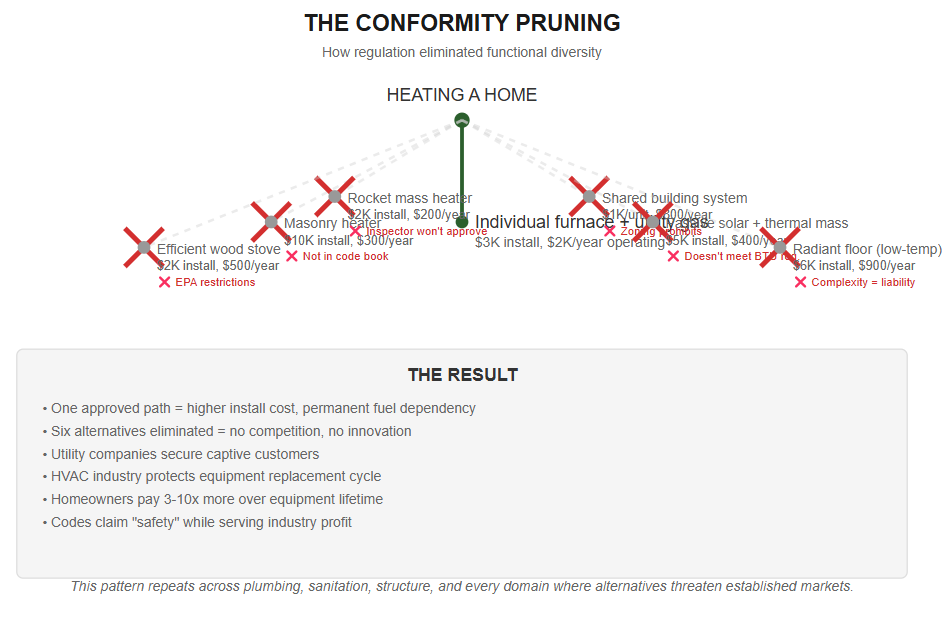

Building codes that prohibit masonry heaters and Russian stoves—proven systems that use 70% less wood than conventional fireplaces while providing 24-hour heat from a single firing—force homeowners into dependence on fossil fuel heating or expensive electric systems. A masonry heater costing $8,000-12,000 to install could replace a $3,000 furnace plus $1,500-3,000 in annual heating costs, paying for itself in 3-5 years. But most jurisdictions won't permit them because inspectors aren't trained to evaluate them, and the HVAC industry has no interest in products that eliminate ongoing fuel sales.

When zoning laws require minimum square footage and prohibit tiny homes, yurts, or modular seasonal structures, they don't protect people—they protect property values and construction industry margins. A well-built yurt costs $8,000-15,000 and can be heated with a small wood stove for $200-400 per winter. A code-compliant minimum house costs $150,000-250,000 and requires $2,000-4,000 annually in heating. The regulations ensure higher construction costs, higher ongoing expenses, and a captive customer base for utilities. Meanwhile, homelessness persists alongside empty land where simple, warm shelter could exist legally.

We don't have six ways to plumb a house or eight ways to heat it because conformity made us stupid. We have one way because regulations crystallized around that way, and entire industries now depend on that monopoly. Every alternative—from composting toilets to greywater systems to rocket mass heaters—faces a wall of code restrictions written with input from the very companies that profit from eliminating competition. The government enforces rules that increase costs and reduce options, calling it public safety while utilities and contractors capture the gains and households pay the premium.

The Mechanism: How Conformity Operates

The pressure to conform doesn't announce itself as censorship. It operates through three interconnected systems that make certain approaches to problem-solving invisible, illegitimate, or simply unthinkable.

Aspiration pressure creates psychological distance between people and anything associated with lower social status. If Indigenous building techniques are coded as "what poor people do," then upward mobility means abandoning those methods—even when they're functionally superior for certain contexts. The desire to signal advancement becomes a force that actively selects against diverse solutions.

Institutional gatekeeping embeds one cultural approach into the regulatory structure itself. Building codes that mandate individual water heaters in every unit, zoning laws that prohibit communal facilities, professional licensing that recognizes only certain training paths—these aren't neutral standards. They're specific cultural assumptions given the force of law, making alternatives literally illegal to explore at scale.

Economic incentives compound the effect. Once markets organize around standardized solutions, the infrastructure to support them becomes self-reinforcing. Manufacturers, supply chains, skilled trades, financing models, insurance products—all calibrated to one approach. Exploring alternatives means swimming against an entire economic current.

What We Actually Lost

The damage isn't abstract. We've eliminated specific functional possibilities across every sector where humans solve problems.

In thermal management, the hierarchy that privileges individual climate control has obscured approaches like strategic building orientation, thermal mass manipulation, earth-coupling, and adaptive clothing systems. Korean ondol floors, Middle Eastern wind towers, and passive cooling designs in traditional African architecture didn't make it into the modern repertoire—not because they don't work, but because they didn't come from the right source.

In water systems, the push for Western-style flush toilets as the mark of development has actively prevented exploration of composting systems, urine diversion, greywater cascading, and closed-loop approaches that could solve sanitation without requiring massive infrastructure investment or clean water waste. The shame associated with "primitive" sanitation has real ecological and economic costs.

In spatial organization, the European model of divided, specialized rooms has replaced flexible, multi-use spaces found in traditional Japanese, Mongolian, and many Indigenous architectures. The result isn't just aesthetic—it's functional. We've lost adaptability, reduced space efficiency, and eliminated social patterns that supported community cohesion and resource sharing.

The Colonial Equation

- European/Colonial approach = advanced, efficient, hygienic, modern

- Indigenous/African/Asian approach = primitive, inefficient, unsanitary, backward

- Psychological cost of exploration = association with devalued peoples + shame + status loss

- Result = entire solution branches never explored

The Feedback Loop

This isn't a static problem—it's self-accelerating. As generations grow up inside normalized systems, the alternatives become literally unthinkable. Students learn building codes, not building principles. They're trained to specify from catalogs of approved solutions rather than reason from first principles about what a space needs to accomplish.

The expertise to implement traditional approaches atrophies. Knowledge held in practice and oral tradition doesn't transfer through academic channels. When the people who understand earth building, reciprocal roof framing, or water harvesting systems die without successors, we don't just lose cultural heritage—we lose technical capacity.

Meanwhile, the problems created by monoculture solutions compound. Energy systems stretched to breaking by universal individual heating. Water infrastructure failing because it was designed around one specific sanitation model. Housing crises partially driven by regulatory frameworks that prohibit lower-cost, community-oriented building patterns.

Beyond Recovery: Expanding the Design Space

The point isn't romantic revival or uncritical adoption of traditional methods. It's recognizing that conformity pressure has created artificial constraints on human problem-solving. We've been searching a narrow corner of the solution space and calling it progress.

Genuine innovation requires access to the full range of approaches humans have developed—not as museum pieces, but as active elements in the engineering toolkit. What happens when we test traditional thermal management with modern materials? What emerges when communal space patterns meet contemporary communication technology? What becomes possible when we stop coding certain solutions as backward and start asking what they actually accomplish?

Key Implications

- Diversity isn't decoration: Alternative approaches represent functional options, not cultural flavor. The loss is operational, not just symbolic.

- Conformity has compounding costs: Each generation that doesn't explore alternatives makes the next generation less capable of doing so. The design space contracts over time.

- Racism operates through omission: You don't need explicit prohibition when shame, aspiration pressure, and institutional gatekeeping do the work automatically.

- Recovery requires active resistance: Simply removing explicit barriers isn't enough. The full weight of normalized infrastructure pushes against exploration of alternatives.

Opening the Space

The work ahead isn't preservation—it's reactivation. It means treating approaches dismissed as primitive as legitimate starting points for innovation. It means building institutions that can evaluate solutions on functional merit rather than cultural origin. It means creating economic pathways that don't require people to choose between exploring alternatives and building viable careers.

Most fundamentally, it requires recognizing that conformity itself is the constraint. Every sector where humans solve problems—from plumbing to heating to social organization—contains vastly more possibility than we've been allowed to explore. The question isn't whether traditional approaches are "better." It's whether we can afford to keep limiting ourselves to one narrow path through an enormous design space.

We're not arguing for nostalgia. We're arguing for options. For the recognition that human ingenuity has produced far more than we've been permitted to use. And that the psychological pressures that pruned our collective toolkit weren't protecting us from inferior solutions—they were protecting a hierarchy that required certain solutions to remain invisible.

The diversity we lost wasn't decorative. It was functional. And getting it back isn't about looking backward—it's about finally being able to look around.